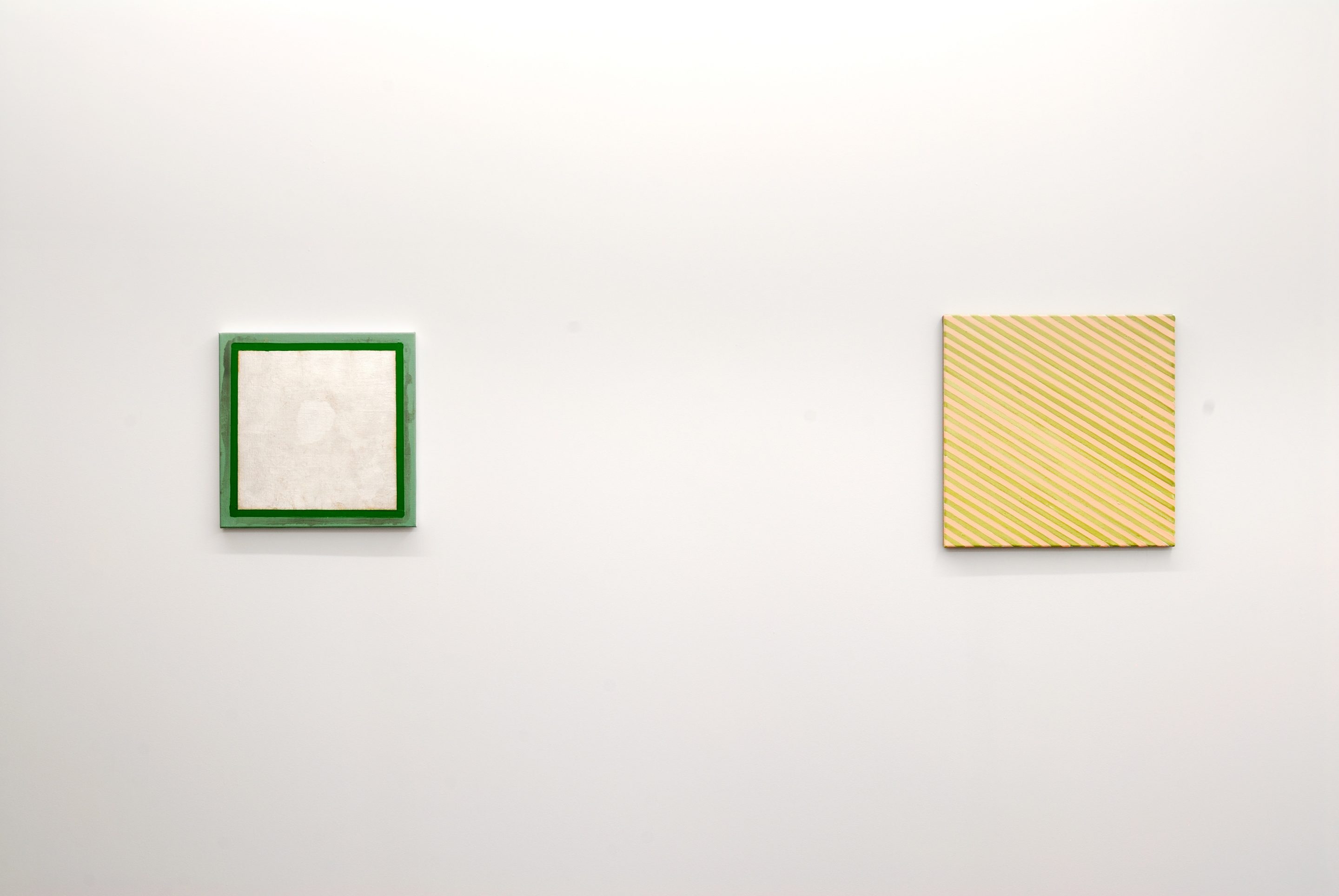

Andrew Barber Studies

Andrew Barber

Studies, 2011

installation view: Hopkinson Cundy, Auckland

Andrew Barber

Monochrome, 2010

oil on sewn linen panels

3400 x 3400mm

Andrew Barber

Studies, 2011

installation view: Hopkinson Cundy, Auckland

Andrew Barber

Study (Elephant's breath), 2010

oil on denim

480 x 480mm

Andrew Barber

Studies, 2011

installation view: Hopkinson Cundy, Auckland

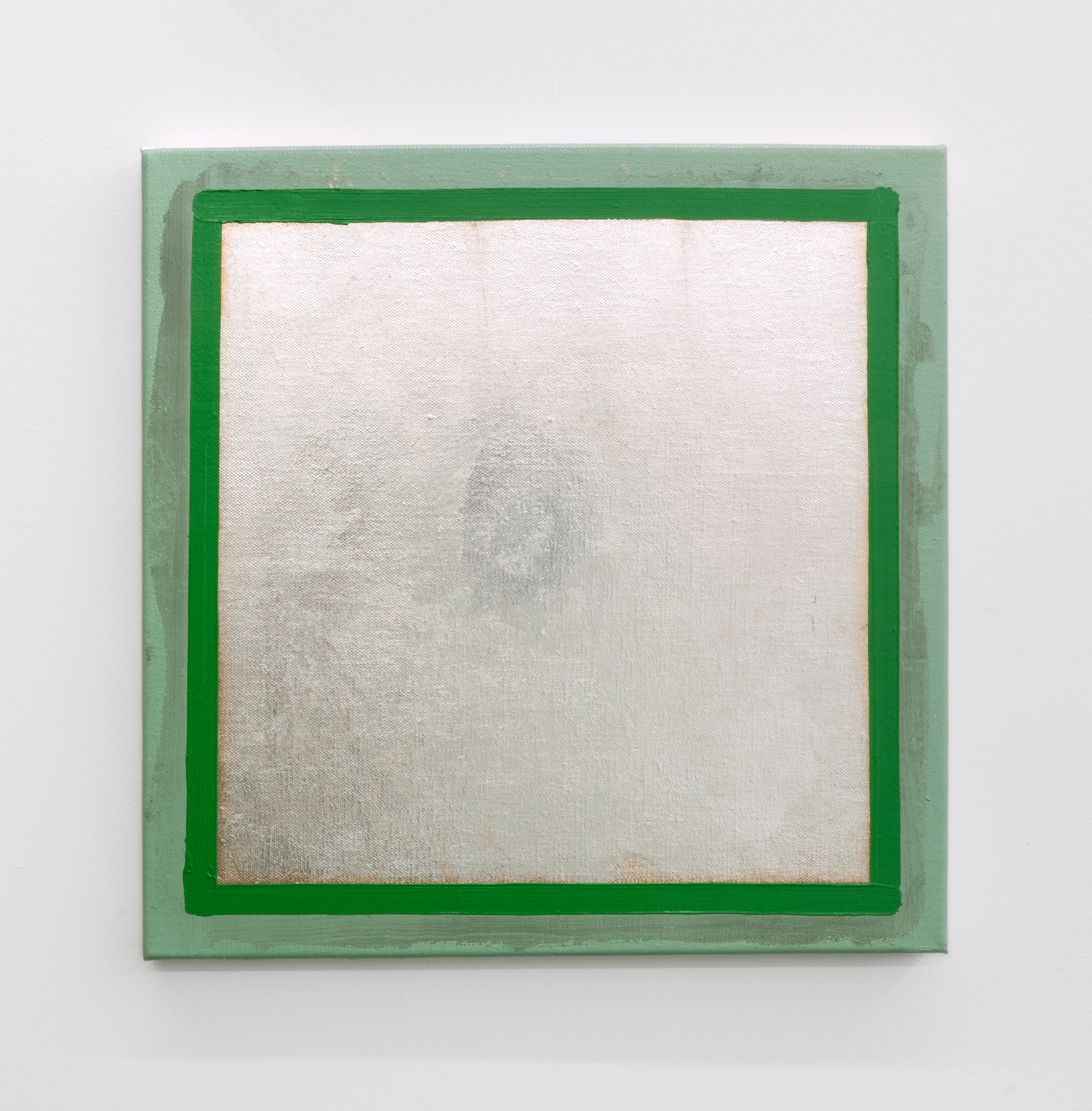

Andrew Barber

Genuine Silver, 2010

oil, silverleaf on linen

535 x 535mm frame

Andrew Barber

Study (Saratoga), 2010

oil on denim

380 x 380mm

Andrew Barber

Studies, 2010

installation view: Hopkinson Cundy, Auckland

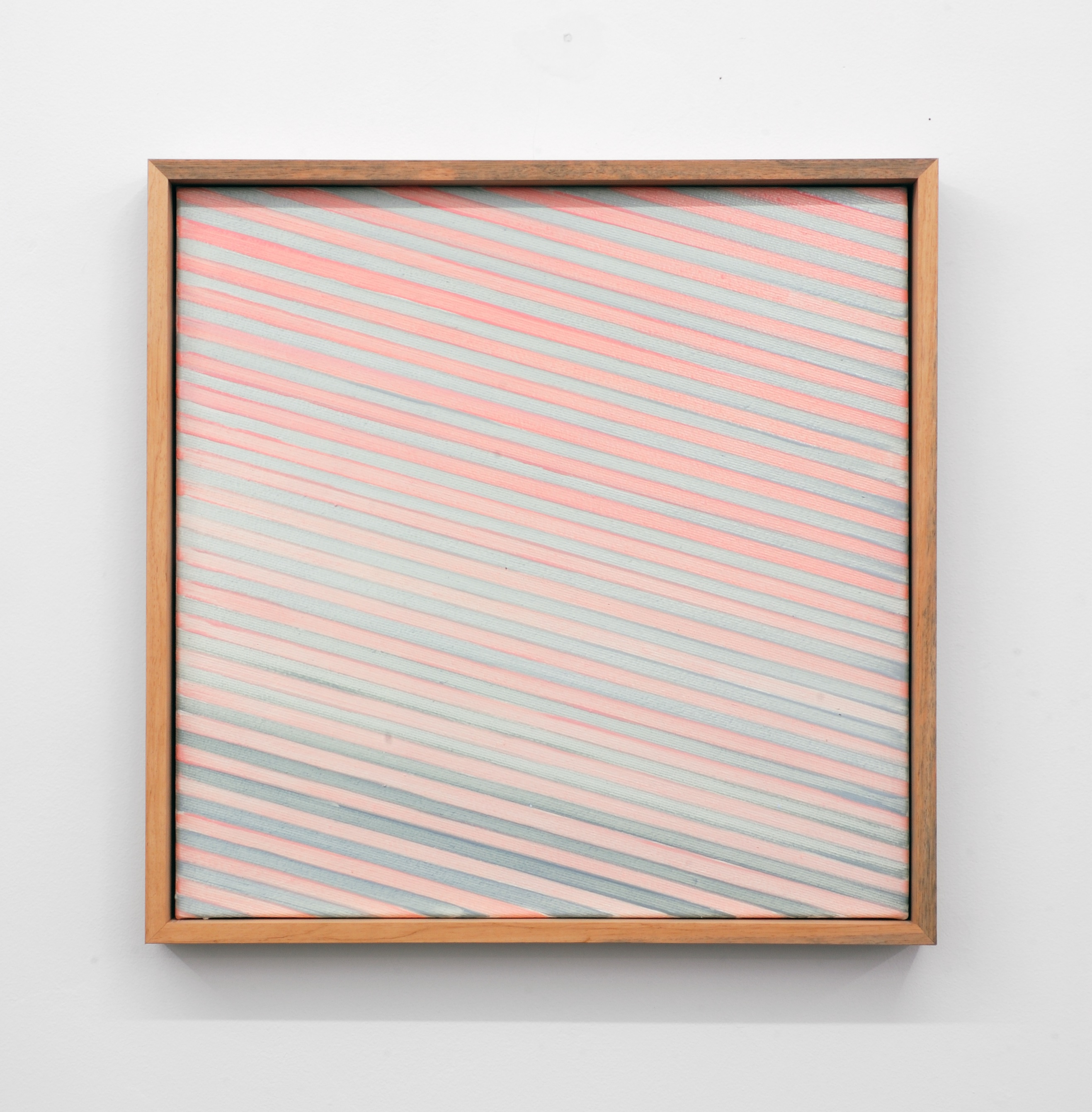

Andrew Barber

Study (For sure she’ll sigh), 2010

oil, silverleaf on linen

380 x 380mm

Andrew Barber

Study (Trailblazer), 2010

oil on denim

500 x 500mm

Andrew Barber

Studies

09 Dec – 29 Jan 2011

Auckland

In Barber’s recent painting specific and often contrary art historical conventions are brought together to inform and blur each other, proposing a practice that is, on one hand, indebted to the privileged tropes of high-church Modernism, and on the other, revels in conflating these styles with their popular derivatives.

Studies features three new large-scale canvasses: Bookend is part colour-field, part hazy landscape; Stiff Blanket is both meticulous grid-painting and tartan picnic blanket; and Monochrome is a geometric abstraction (constructed from sewn linen panels) that could also be a cloudless skyscape. Architectural in scale, with the largest canvas measuring over 3 x 3 meters, Barber’s new work remembers the complex relationship between the pictorial and physical proposed by his expansive Wall Paintings of 2006/2007, where the artist-as-tradesman worked directly with existing architecture to create a one-to-one scale plan of a space as imposing minimal monochrome. However, the title of Barber’s new show negates the impressive scale of the large paintings, designating all work as preliminaries. Studies presents painting as an open-ended process in constant transition, free to play in art history’s gaps and overlaps, ironies and idiosyncrasies.

Andrew Barber is now represented by Hopkinson Cundy. Studies is Barber’s first solo show at the gallery and will be accompanied by a short essay by Auckland-based writer Gwyn Porter.

Andrew Barber (b. 1978) currently lives and works in Auckland, New Zealand. Recent exhibitions include: Two Man Shoe, Peter McLeavey Gallery, Wellington (2010); Wall Painting #3, Te Tuhi, Pakuranga (2009); Picnic, 30-32 Customs St, Auckland (2009); Dreamhome/Shithouse, Gambia Castle, Auckland (2009); Lean, Starkwhite, Auckland (2008). Barber’s work has also been represented in: Leisure Suite, LeRoy Neiman Gallery, New York (2008); Headway: New Artists show, Artspace, Auckland (2006); and in Speculation, the publication project for the 2007 Venice Biennale. In 2011 Barber will make solo exhibitions at Peter McLeavey Gallery, Wellington and Y3K Gallery, Melbourne.

Painters don’t usually measure up a space first, approaching it as a tradesman might, with a certain obliviousness to the grand traditions of painting. Moving with the desensitised transience that is expected, the paintings’ proportions are dictated by that of the room. They figure enactments of materials that are usually ignored out of a customary distaste for interior design.

What is remarkable is that the object is a commitment, at least in its physicality. Moving from one house to another, villageless, is a blessing, like chronic pain and bad tattoos that don’t go away. A lesson in mindfulness, we learn to detach from feeling, to live in other parts of our brain, and to regard ourselves from the observer position. I am painting now. I am walking now. I am looking at painting now, etc.

Rental property – something good must come of this. When a friend and I would rent out-dated luxury houses that were on the market, I would lean paintings and framed works against the walls. This removed the need to make a set of decisions about nails and holes and this meta-alcoholic aesthetic (the root of which is not in a substance but rather in leaving) reminded me to enjoy that avocado green cut-pile carpet.

The first piece of writing I ever did in finished form was in high school in a class called “static images”. Our first assignment was to write automatically about an album cover the teacher put up. It was the Fleetwood Mac album, deeply uncool, the one with Mick Fleetwood on the cover with the pom poms hanging down between his legs on long strings.

The second assignment involved choosing a type of image and analysing it. I was really interested in text-only newspaper real estate advertisements. That was my first mistake, if you consider it a mistake to receive a bad mark. They literally wanted “images”. I went to the university library and presented a pretty great analysis of aspirational language and ego fortification and totally failed.

Some paintings make worlds that continue. Others are finished and the entity moves on. That will do: enough colour, enough detail, lessons in stillness, or punctuation. The lightning goddess, her isolation, the way she can fit in anywhere, her problems, is not everyone’s bag. Without her, the typologies or ontologies of painting, its method and materials are in repose.

Duly, an artist can give a lesson in painting a window frame perfectly that takes more than three hours. A space can be sanded so thoroughly that the dust created and the way it films everything engenders a feeling of betrayal. This sort of shedding or atomisation of what is supposed to be solid should be done in private and not talked about some might say.

There is no conceptual uptightness, but something more physical and material. John Baldessari made a work in 1977 in which he filmed himself from above painting a small room over and over again in different colours. Of Six Different Inside Jobs he said, “This could be some kind of a painter’s hell.” He had, as a teen, painted houses for his landlord father and divulged that “painting is essentially work with a small amount of pleasure attached.”

Repetitive, well-guessed actions can get the mind in the right place in the head cavity. If you hold one of your fingers with your other hand, your mind hovers towards the centre and rests. Likewise, if you look downward, out both eyes at the same time, activity slides on an axis to the back of the brain and everything relaxes. At first this may make you feel a little ill until you get a taste for how it feels.

Gwyn Porter, November 2010