Dane Mitchell Tuning

Dane Mitchell

Tuning, 2018

brass, plated aluminium, Perspex, electronics, radio transmitter, coaxial cable

3410mm x 8300mm

installation view: Hopkinson Mossman, Wellington

Dane Mitchell

Tuning, 2018

brass, plated aluminium, Perspex, electronics, radio transmitter, coaxial cable

3410mm x 8300mm

Dane Mitchell

Tuning, 2018

brass, plated aluminium, Perspex, electronics, radio transmitter, coaxial cable

3410mm x 8300mm

Dane Mitchell

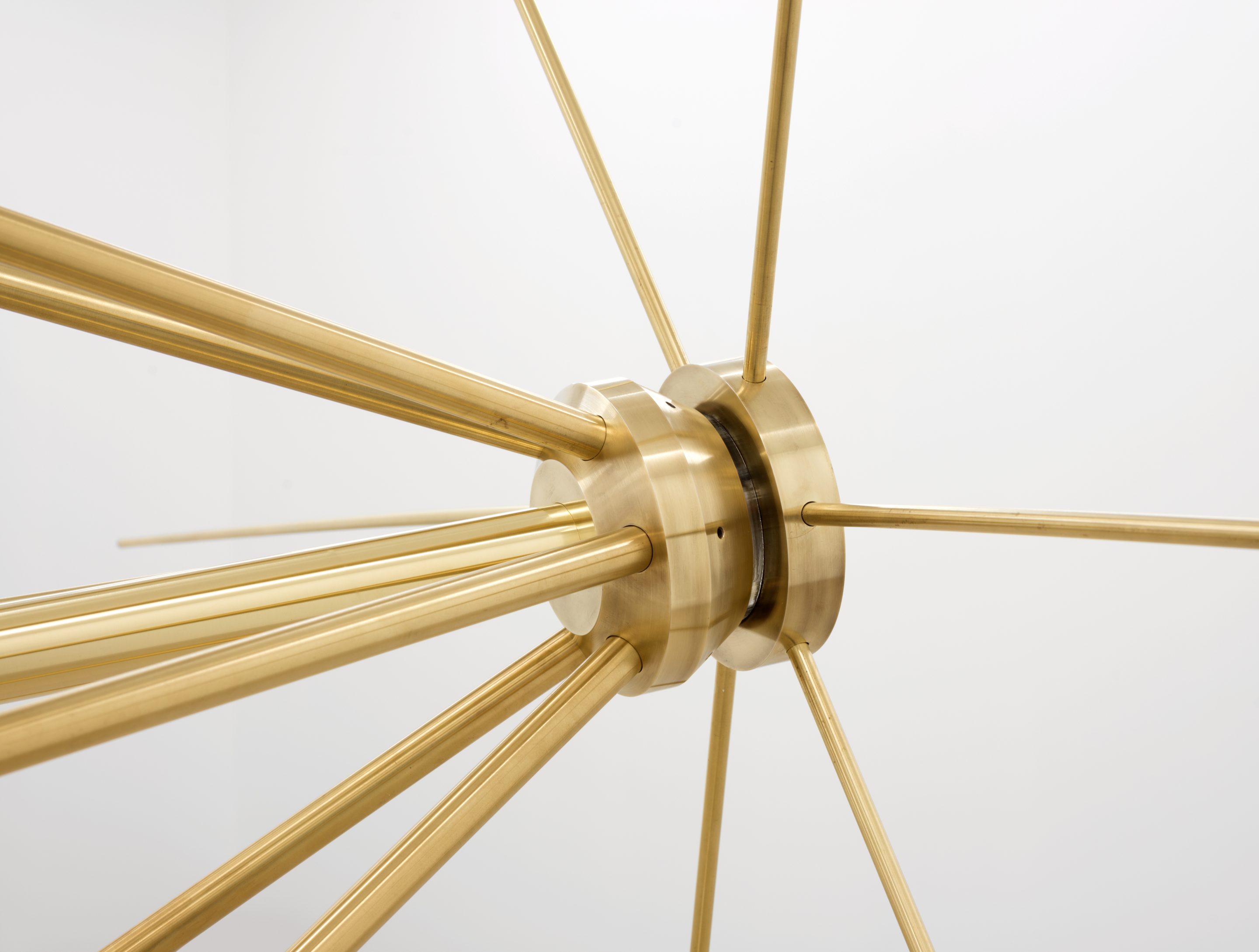

Tuning (detail), 2018

Dane Mitchell

Tuning (detail), 2018

brass, plated aluminium, Perspex, electronics, radio transmitter, coaxial cable

3410mm x 8300mm

Dane Mitchell

Tuning, 2018 (detail)

Dane Mitchell

Tuning, 2018

brass, plated aluminium, Perspex, electronics, radio transmitter, coaxial cable

3410mm x 8300mm

Dane Mitchell

Tuning

13 Sep – 13 Oct 2018

Hopkinson Mossman Wellington is pleased to present Tuning, a solo exhibition of new work by Dane Mitchell.

Working with a wide-range of mediums including dust, scent, bacteria, occult practices, and radio transmissions, Mitchell’s practice is concerned with invisible or almost-invisible forces and substances. His sculptures and installations tease out the potential for things to appear and disappear, testing the boundaries of empirical knowledge and rational thought.

For Tuning, Mitchell presents a large brass discone antenna that occupies the entire Hopkinson Mossman gallery space. Usually mounted vertically, a discone antenna has a wide frequency range that makes it attractive in commercial, military and amateur radio applications, and permits it to broadcast undesirable emissions from faulty or improperly filtered transmitters. In Tuning, Mitchell’s antenna is connected to a transmitter, generating an electromagnetic field across FM bandwidth. The audio-transmission is a ‘spurious emission’ (a term for any radio frequency not deliberately created or transmitted); a sound that is camouflaged in the broadcast spectrum amongst background noise, and presents as static or white noise.

The transmissions emanating from the antenna are temporal sequences, they can be ‘read’ or captured in sonic form, but they are invisible to the eye. In Tuning, the artwork stretches well beyond the physical, entering the broadcast space as a transmitted radio signal, spreading itself invisibly into the world. When tuned into it potentially introduces an infinite number of transmissions from beyond the gallery walls, disestablishing the boundaries that artworks traditionally maintain. The space between object, gallery, and viewing body is here imagined as something active and constantly in flux.

Writing in 1962 George Kubler made the poetic suggestion that astronomers and historians are both concerned with appearances noted in the present, but occurring in the past (light takes millions of years to reach astronomers on earth, historians deal with narratives and objects from the past). He suggests both astronomers and historians collect ancient ‘signals’ from ‘objects and starlight alike’. When a star dies and its light goes out the gravitational effect of the missing star is still perceptible, taken further, one could say that when an artwork is gone (destroyed, or perhaps sold) one can still detect its perturbations upon other bodies in the field of influence.

Tuning works in this legacy to build a complex analogy for the processes already at play in the perception of an artwork, in particular the reliance on the expectation, imagination, and belief of the viewer. Mitchell stretches our imaginations to simultaneously conceive of the work as both an existing object (encountered conventionally in the gallery space), as well as being a metaphorical transmitter of a ‘signal’ that hides amongst the background white noise.

Dane Mitchell (1976, Auckland) has presented solo exhibitions both nationally and internationally in Germany, France, Brazil, The Netherlands, Switzerland, Hong Kong, Australia, United States and New Zealand. He has also participated in a number of biennales, including Biennale of Sydney 2016, Australia; Gwangju Biennale 2012, South Korea; Liverpool Biennial 2012, United Kingdom; Singapore Biennale 2011e; Ljubljana Biennale 2011, Slovenia; Busan Biennale 2010, South Korea and the Tarrawara Biennial 2008, Australia. Recent exhibitions include: Iris, Iris, Iris, Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tāmaki, Auckland, and Mori Art Museum, Tokyo (2017/2018); OTIUM #3, Institut d’art Contemporain, Lyon (2018); Thailand Biennale, Karbi (forthcoming 2018); Play Kortrijk, Belgium (2018); Communicating Vessels, Galeria Bunkier Sztuki, Kraków (2017); Occulture: The Dark Arts, City Gallery, Wellington (2017); Aeromancy, Hopkinson Mossman, Auckland (2017); Biennale of Sydney: The future is already here—it’s just not evenly distributed (curated by Stephanie Rosenthal), Sydney (2016); Art and the City: Zuricher Kunstfestival, Zurich (2016); Exploded Worlds, Dunedin Public Art Gallery, Dunedin (2016).

Dane Mitchell is New Zealand’s representative for the 58th Venice Biennale in 2019.

Ground to Air: Dane Mitchell’s Tuning

By Simon Gennard

In the beginning is the noise; the noise never stops. It is our apperception of chaos, our apprehension of disorder, our only link to the scattered distribution of things. (1)

It’s nearly impossible to say where the object ends. The object, a discone antenna, is balanced on the floor of the gallery, constrained by earthly considerations — the dimensions of the room, and the service elevator, the strength of the ground beneath it. Introduce a radio, though, and we learn that the object keeps going. It transmits a noise: white noise. To untrained ears, what is transmitted by the work is indistinguishable from noise transmitted across an entire spectrum of unclaimed frequencies. It’s difficult, then, to pinpoint exactly where the transmitter’s power is exhausted. The object insinuates itself in the atmosphere. Wherever there is noise, so we might find the object.

Dane Mitchell describes it as a kind of infection, which, like a virus embedding itself in existing cells and mutating their structure according to its own ends, transforms the space around the object — the gallery, the building, the street below — into sculptural space. We inhabit the work, we can’t help but do so. Its waves move through us. It may not be outside of the realm of possibility to say, even, that our presence alters what can be heard; that the density of bodies around the object alters the patterns and velocity of the vibrations transmitted by the object, even if only slightly.

There’s no semantic arrangement in this sound, but it’s not without meaning, nor is it without form. It’s made of vibrations from objects in proximity: fluorescent lights, computers, residual energy from faraway lightning strikes, even the violent beginning of the universe. It tells us firstly that radio antennas are hungry and undiscerning; that they make no distinction between human voices and the humming of machines. It tells us that the earth is restless. It tells us that noise, in some form or another, is always waiting to interfere in the transmission of information. It’s at the edges of every transmission, threatening to rupture meaning as it makes its way from transmitter to receiver, person to person.

Mitchell’s practice takes place at peripheries of thought. His material is the invisible or almost invisible, the almost unthinkable, that which is cognisable as a fleeting moment, a change in the air, but is barely able to be articulated. Meaning, in Mitchell’s work, seems delicate, contingent. His work unsettles an epistemological regime that prioritises sight, in favour of making things known through baser senses. Here, the artwork is a signal. It transmits electromagnetic waves, yes, but it also transmits something else along perceptual, affective channels.

All artworks transmit information, of course. And all artworks depend on an existing infrastructure for meaning to be carried; an infrastructure constituted by the histories of what art has done and been in the past, what it is allowed to be in the present. For Boris Groys, one of the things art might do in the present is intervene in the motion of technological progress, peer past its heady rhetoric, and reveal the ideological mechanisms at play. ‘By stopping technological progress at least for a moment,’ Groys writes, summarising Heidegger, ‘art can reveal the truth of the technologically defined world and the fate of humans inside this world.’ (2)

Here, though, it’s not progress that Mitchell halts. The discone antenna is plucked from radio’s history. First invented in 1943, the discone antenna is ancient, as far as telecommunications technologies are concerned. Formally, its brass plating, its thin prongs reaching out into space, conjure the kind of technological optimism that seemed legitimate in the middle of the twentieth century. Squint and it looks like an earthly Sputnik. The signal transmitted by the work is fuzzy. Energy congeals around it, interfering in the reception of meaning. It brings with it a century or more of history of technological invention and the ideologies embedded within those technologies.

There are episodes in the history of radio which typify a technological utopianism that now seems naïve. In 1912, when radio was still relatively new, Guglielmo Marconi, often considered the grandfather of radio technology, is quoted in an article in Technical World Magazine outlining a socialist vision made possible by wireless technology, ‘Within the next two generations,’ he says, ‘we shall have no only wireless telegraphy and telephony, but also wireless transmission of all power for individual and corporate use, wireless heating and light, and wireless fertilising of fields. When all that has been accomplished — as it surely will be — mankind will be free from many of the burdens imposed by present economic conditions.’ (3) Marconi was wrong, or at least, he remains wrong for now. Radio and its subsequent developments succeeded in collapsing space and time, in making the world intimate and always available, but it hasn’t quite restructured relations of labour, property, and prosperity. It’s not the accuracy of Marconi’s prediction that interests me here, though, it’s what travels alongside it. Embedded in this optimistic pronouncement is a belief that the world exists to be mastered, that it is through progressive innovation that we might tame the world, and thereby find liberation.

Since Marconi’s pronouncement, wireless transmissions have become ubiquitous, probably in ways he could not have predicted. We inhabit a landscape dense with waves carrying information in all directions. These waves remains fickle. Radio needs frequent retuning, wifi routers need resetting. Electromagnetic waves remain vulnerable to atmospheric conditions or dense materials, to trees, to rain and storms, to concrete, to metal. Drive through a tunnel, or angle an antenna in the wrong direction, and the voice one expects to hear across FM bandwidth risk being swallowed by noise. So it might not be a stretch to say that rather than using radio to master the world, we’ve learned to live within radio’s limitations.

The discone antenna, I learn, is recommended by at least one doomsday prepper on YouTube as a post-apocalyptic communications device. It’s robust, and able to transmit and receive signals across a wide range of frequencies. Prepping has its own pretensions of mastery. It casts the world as hostile, and always on the edge of rupture, and in response presents strategies for individual continuity. Here, Marconi’s prophecies turn dark. Technology and its attendant discourses finds themselves transformed into being our salvation, into being our downfall. In the face of ecological collapse, epidemics, alien invasions, class wars, race wars, preppers turn inwards, to make their world small enough to exert sovereignty over.

Mitchell’s antenna doesn’t seem to be reaching for mastery. Its scale is beyond human, but, balanced on its side, it seems tamed. The noise it transmits has a name. It is a spurious emission. The term designates any frequency not deliberately created or transmitted. The sound makes its way into the atmosphere without intent, and without hope of making sense to human ears. It hides itself, at least to those who aren’t listening for it. Mitchell’s work, like any signal, doesn’t travel alone. Interfering in its transmission are century-old visions of the future, as well as more recent ones, the humming from fluorescent lights, lightning strikes, the violent beginnings of the earth, and its violent end. In Mitchell’s case, though, this interference doesn’t seem to threaten the legibility of the work, rather, it seems essential to its meaning.

Notes:

- Michel Serres, The Parasite, trans. Lawrence R. Schehr, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1982, p. 126.

- Boris Groys, ‘The Truth of Art,’ e-flux 71, March 2016.

- Ivan Narodny, ‘Marconi’s Plans for the World,’ Technical World Magazine, October 1912, pp. 145, accessed via https://earlyradiohistory.us/1912mar.htm, last accessed 2 September 2018.