Nicholas Mangan Nauru, Notes from a Cretaceous World

Nicholas Mangan

Dowiyogo’s Ancient Coral Coffee Table, 2010

coral limestone from the island of Nauru

1200 × 800 × 450mm

Nicholas Mangan

Nauru, Notes from a Cretaceous World, 2009

HD video (colour, sound)

duration 12min 27sec

Nicholas Mangan

Nauru, Notes from a Cretaceous World, 2009

HD video (colour, sound)

duration 12min 27sec

Nicholas Mangan

Nauru, Notes from a Cretaceous World, 2009

HD video (colour, sound)

duration 12min 27sec

Nicholas Mangan

Nauru, Notes from a Cretaceous World, 2009

HD video (colour, sound)

duration 12min 27sec

Nicholas Mangan

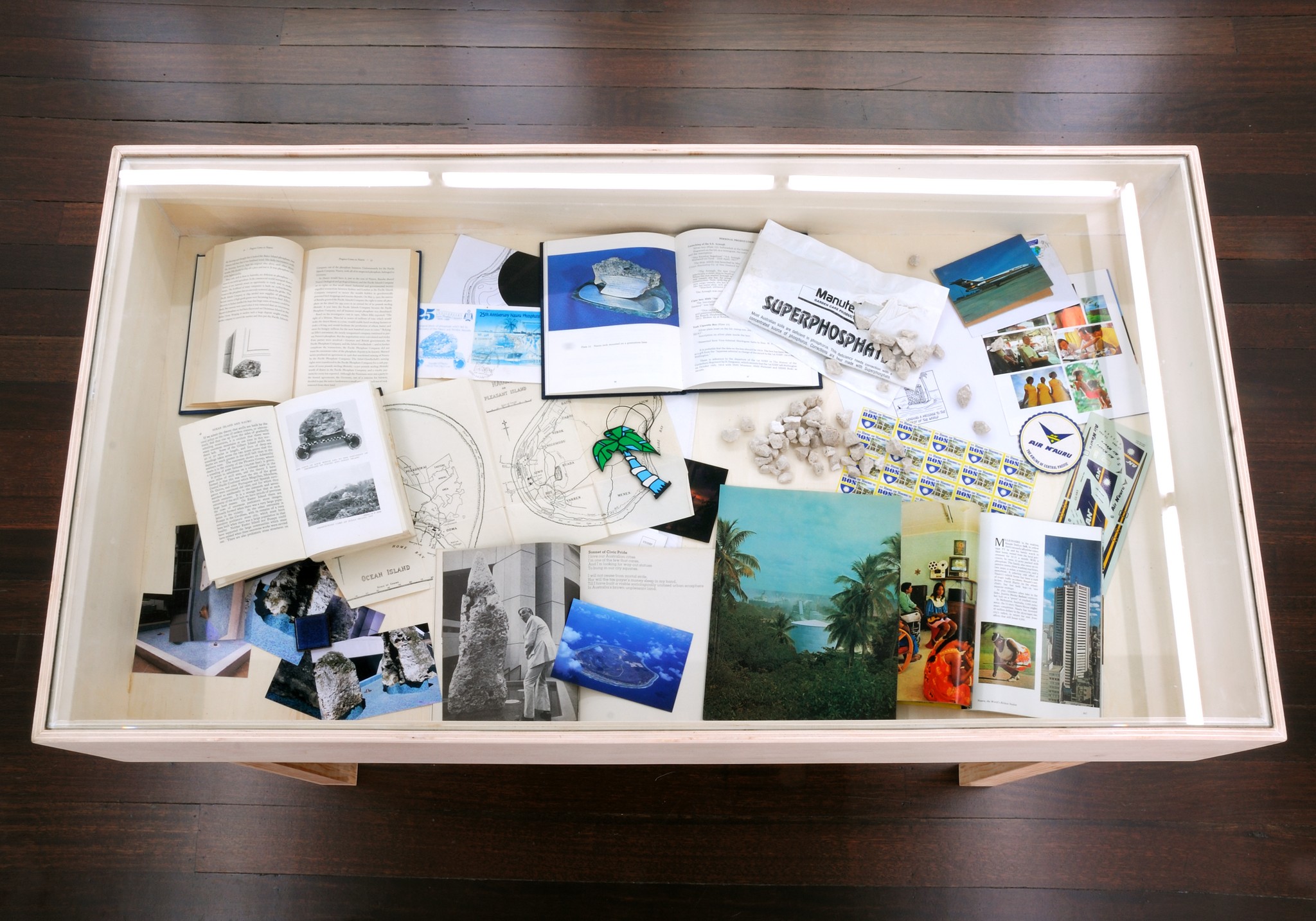

Pacific Sediment, 2009

found material in vitrine 900 x 1380 x 740mm

Nicholas Mangan

Nauru, Notes from a Cretaceous World

06 Nov – 04 Dec 2010

Auckland

Hopkinson Cundy’s inaugural exhibition, Nauru, Notes from a Cretaceous World, comprises a new film and sculpture by Melbourne-based artist Nicholas Mangan.

Mangan’s film recounts the stranger-than-fiction story of the nation formerly known as Pleasant Island, and the eventual collapse of its fortune, through the shifting fates of three pinnacle rocks that once guarded the entryway to Melbourne’s Nauru House – a fifty-two-storey skyscraper built during Nauru’s mining-royalty boom.

The short film is accompanied by a singular sculpture – a table fashioned from a slice of distinctive Nauru limestone. In this work, Mangan realises the seemingly absurd moneymaking scheme suggested by Nauru’s then President Dowiyogo (with bankruptcy looming after strip-mining had exhausted the island’s phosphate supplies) that the totem-like rock pinnacles littering the island be cross-sectioned, polished and sold as coffee tables.

As Fayen D’Evie says in her short essay that accompanies the exhibition: “As usually caricatured, Nauru’s rise and fall from capitalist grace is a study in human folly and pathos. In his film Nauru, Notes from a Cretaceous World, Mangan shifts the focus to terrestrial characters. He reveals the ancient cycles of life, excretion and fossilised death that formed Nauru’s pinnacle rocks, embedding alluvial and rock phosphate in the process. In Mangan’s mythmaking, the absurdity of human intervention on Nauru diminishes to a thin time slice in the island’s geologic evolution.”

Nicholas Mangan was born in Geelong in 1979, studied and now lives in Melbourne, Australia. Recent solo projects include: Between a rock and a hard place, Art Gallery of New South Wales, Sydney; A1 Southwest Stone, Gertrude Contemporary Art Spaces, Melbourne; and Comparative Material, Sutton Gallery, Melbourne. Mangan’s work has been included in various international group exhibitions such as Lucky Number Seven, SITE International Biennial, Santa Fe, New Mexico; The Shadow Cabinet: the second phase of “Master Humphrey’s Clock”, de Appel Arts Centre, Amsterdam; Lost and Found: an archeology of the present, TarraWarra Biennial, Melbourne; and Uncanny Nature, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA), Melbourne.

Nauru, Notes from a Cretaceous World coincides with the New Zealand launch of a new monograph on Mangan also titled Notes from a Cretaceous World, featuring a two-part essay by Shelley McSpedden.

Rot and Reinvention in the Nation Formerly Known as Pleasant Island

During the 1970s, newly independent Nauru basked in its status as the second wealthiest country per capita in the world. For fifty years, New Zealand and Australia had exploited their role as Nauru’s colonial Protectors, fleecing the island of phosphate to supercharge antipodean farms. Now they had become paying customers. As mining royalties flooded into the world’s smallest island state, no extravagance was off limit. The President splashed out on yachts and a fleet of Boeings, which he commandeered at whim. Luxury cars crowded the island’s single paved road. The police chief imported a yellow Lamborghini only to discover he was too large to fit behind the wheel. The leaders of Nauru happily flaunted their riches to their former colonial overlords. In Melbourne, they constructed a fifty-two-storey skyscraper, the tallest building in the downtown, and humbly christened it ‘Nauru House’.

As a child, Nick Mangan watched enormous bulk carriers dock at Geelong port, laden with raw phosphate heading for a local processing plant. But by the 90s the phosphate had been mined to near exhaustion. Eighty percent of the island had been stripped of topsoil and turned into uncultivable badlands dominated by craggy limestone pinnacles. Lavish spending, embezzlement and fanciful investing had propelled Nauru to bankruptcy. The government resorted to selling passports and laundering money for the Russian mafia to make ends meet. When such dubious ventures attracted international sanction, the leaders of Nauru canvassed for new moneymaking industries. One proposal, described by then President Dowiyogo, presumably sarcastically, advocated that the pinnacles be cross-sectioned, polished and sold as coffee tables. Instead of pinning Nauru’s future on wasteland repurposed as home furnishings, Dowiyogo’s successor enthusiastically brokered a deal to host Australia’s asylum seekers. Still, the debts piled up. The government of Nauru rapidly acquired and defaulted on loans, and was evicted from its namesake Melbourne tower by a furious creditor.

As usually caricatured, Nauru’s rise and fall from capitalist grace is a study in human folly and pathos. In his film Nauru: Notes from a Cretaceous World, Nick Mangan shifts the focus to terrestrial characters. He reveals the ancient cycles of life, excretion and fossilised death that formed Nauru’s pinnacle rocks, embedding alluvial and rock phosphate in the process. In Mangan’s mythmaking, the absurdity of human intervention on Nauru diminishes to a thin time slice in the island’s geologic evolution. Mangan recounts the collapse of Nauru’s fortune through the shifting fates of three pinnacle rocks shipped to Australia from Nauru and erected at the entryway to Nauru House as totemic swagger. When the creditor moved in, the rocks were unceremoniously deposed. The Australian spokeswoman for Nauru claimed them as garden ornaments for her holiday house. Mangan spied the rocks, convinced her to sell one, and fashioned it into three small tables, realising Dowiyogo’s vision.

Mangan’s fascination with geology dates back to the rock collection of his grandfather who worked in Geelong quarry: “He kept them on a set of shelves in his garage. All of the rocks were about the size of a lemon. They would fit in the palm of my hand.” One scene of Mangan’s film features a lump of rock mounted on an ornate pedestal. A plaque proclaims it to be the original rock that launched Nauru’s phosphate industry. Foraged by a trader as possible raw material for manufacturing children’s marbles, the rock was abandoned for many years to a homely though functional life as a doorstop, until a new employee noticed it and tested its chemical make-up. A fragment of that original rock now languishes somewhere in the catacombs of Massey University, donated by the family of former Prime Minister ‘Farmer Bill’ Massey, who had acquired it as a memento of his finest achievements. A 1926 article in NZ Truth, captioned ‘Helping the Green Grass to Grow All Around’ praises the sound statesmanship of Massey, “who, it will be remembered, secured for New Zealand 16 per cent of the output of wonderful Nauru Island”.

The awkwardness of postcolonial relations has been a recurring target for Mangan, as described in a monograph, also called Notes from a Cretaceous World. In the book, Mangan includes a reference image from Dennis O’Rourke’s documentary The Cannibal Tours, which trails a group of eco-tourists cavorting through Papua New Guinea. In the image, a grinning man sports a sunhat with a leopard print band. Another has a camera slung around his neck, primed to photograph ‘primitive’ customs. Two women have their faces painted in ‘native fashion’. In his film, Mangan presents contemporary Nauru through exquisite, depopulated scenes: clusters of palm trees, concrete ruins, rusting equipment. Despite the obvious decay, the footage mimics a holiday slideshow.

Fayen D’Evie