Nicola Farquhar New Paintings

Nicola Farquhar

New Paintings, 2011

installation view: Hopkinson Cundy, Auckland

Nicola Farquhar

Amanda, 2011

oil on canvas

450 x 350mm

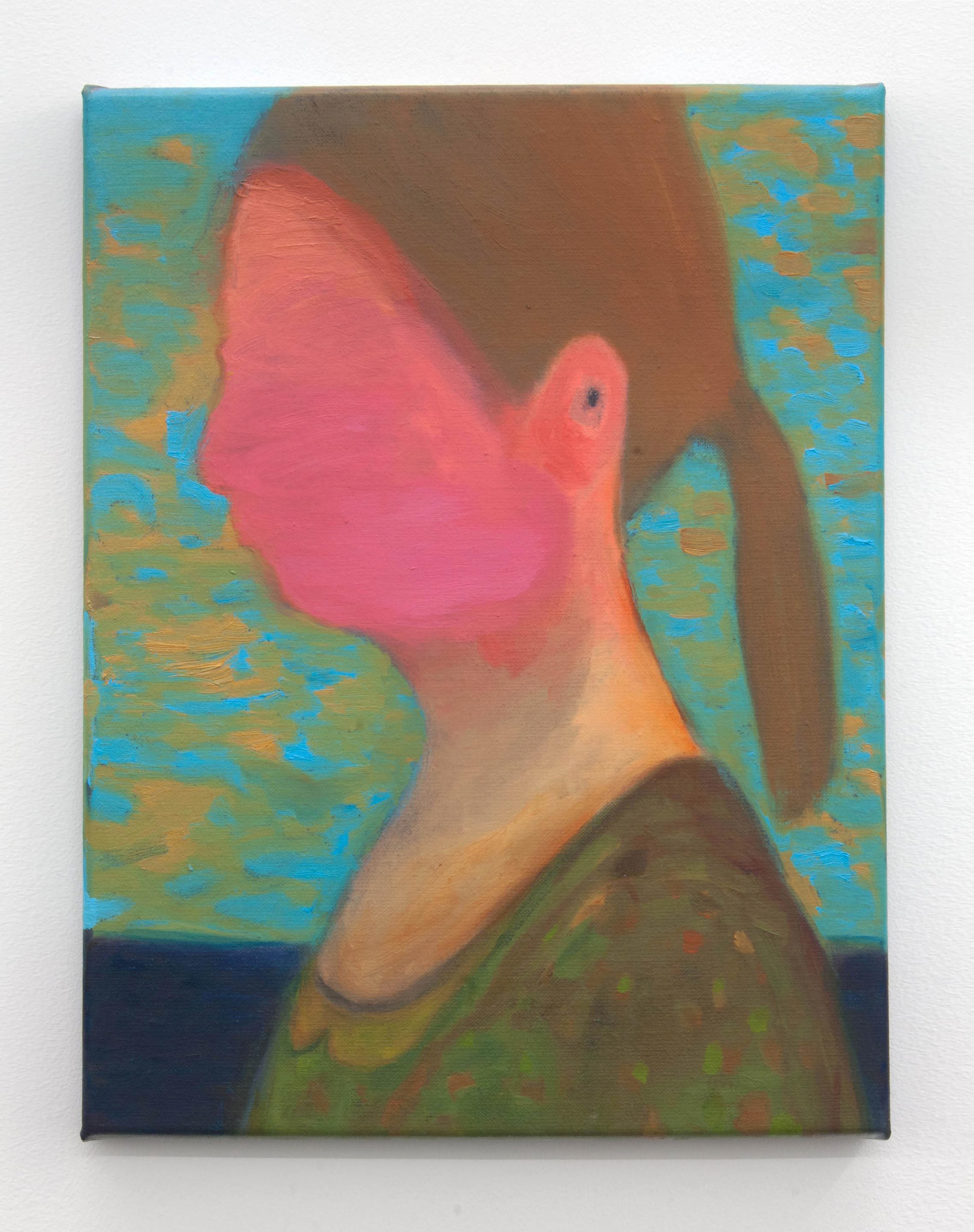

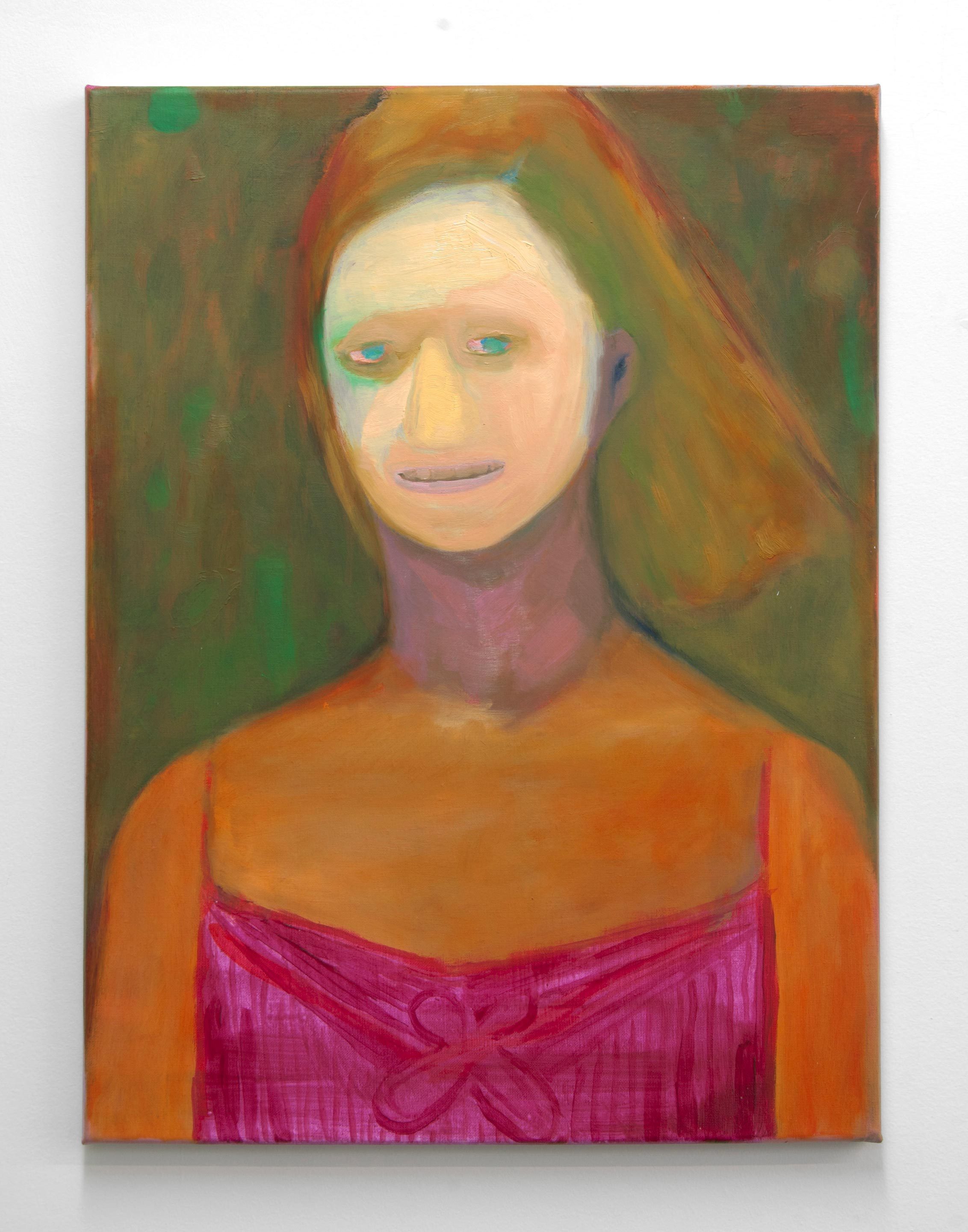

Nicola Farquhar

Katy-Lee, 2011

oil on canvas

580 x 470mm

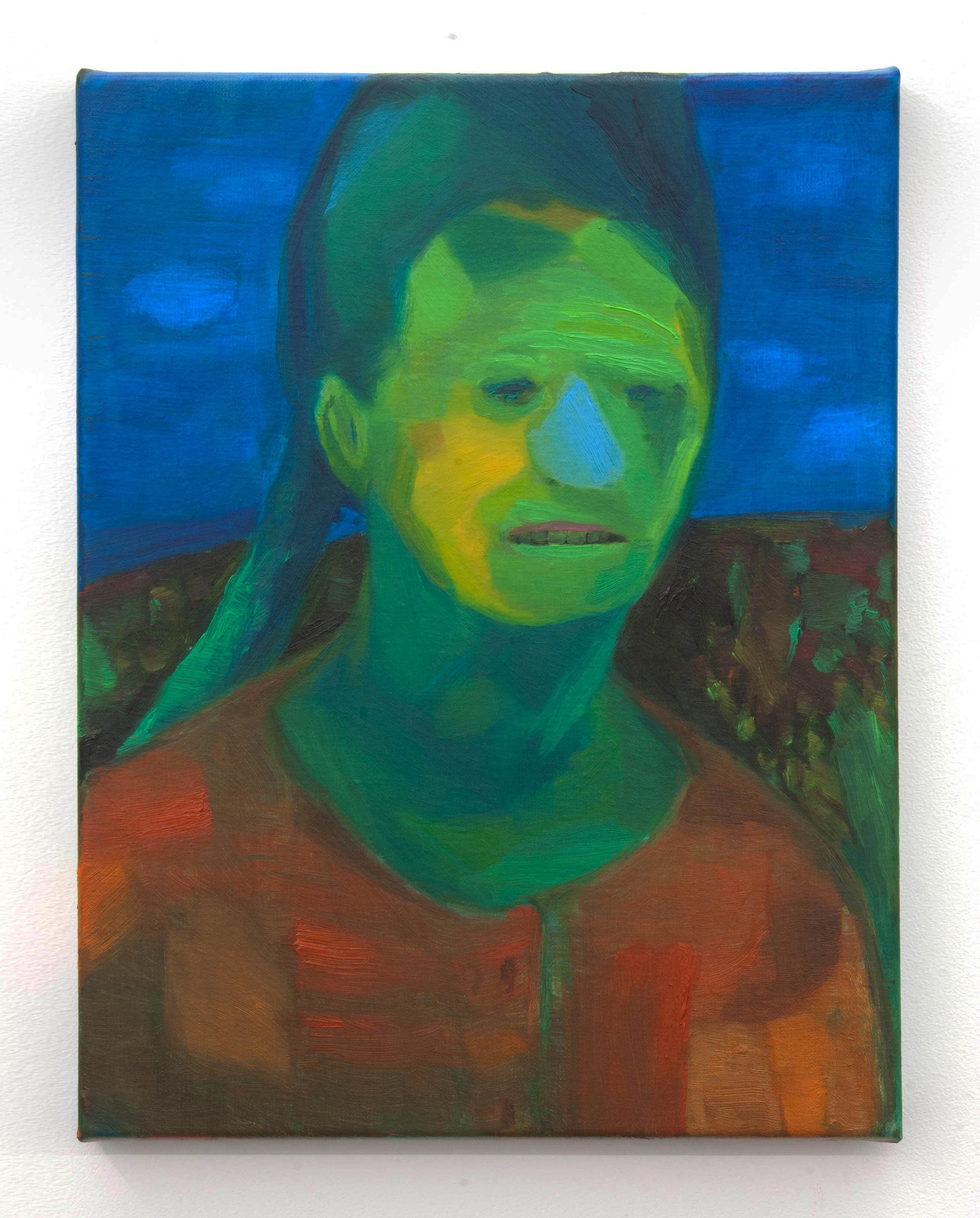

Nicola Farquhar

Joanne, 2011

oil on canvas

450 x 350mm

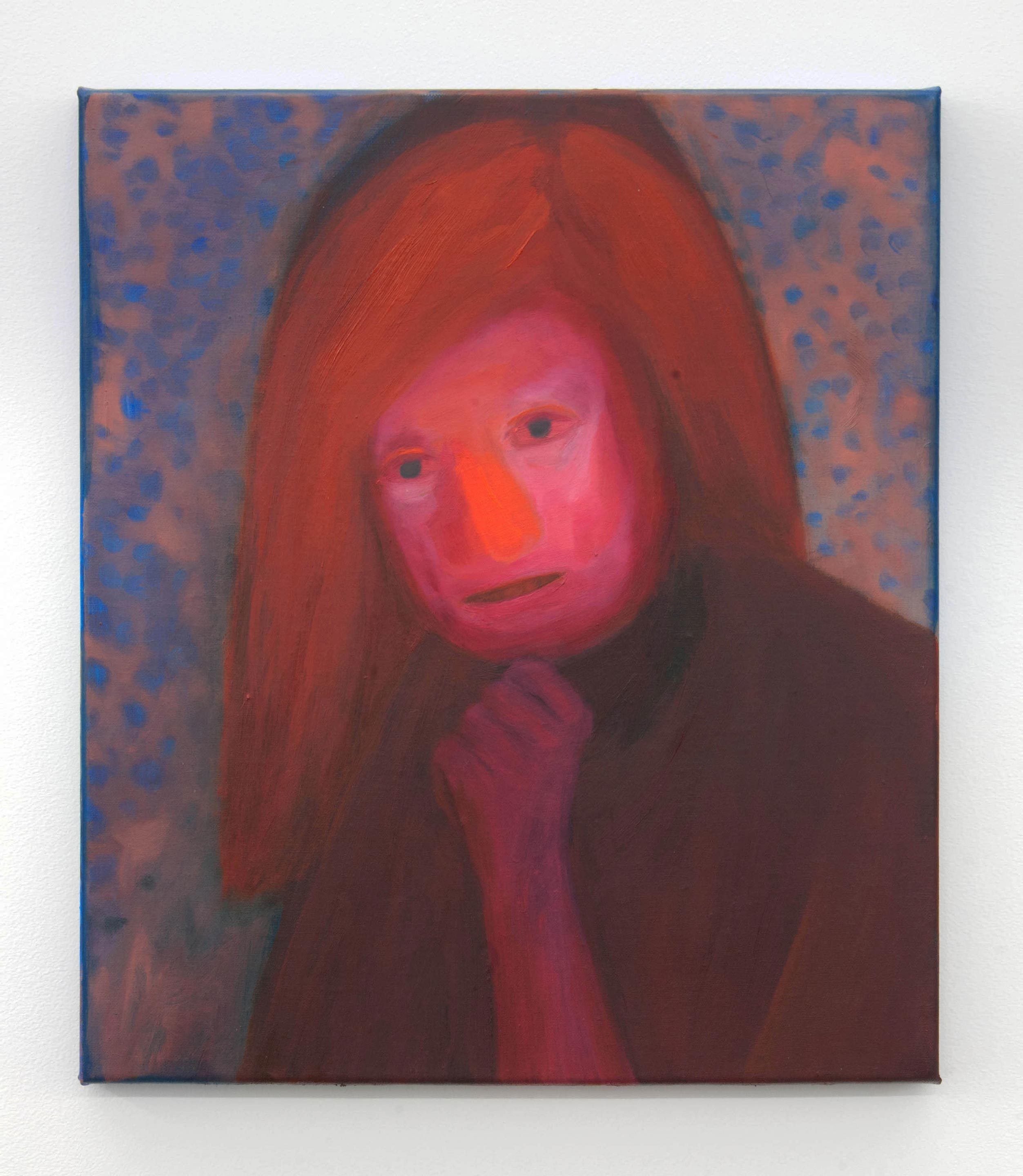

Nicola Farquhar

Katy-Lee, 2011

oil on canvas

450 x 400mm

Nicola Farquhar

New Paintings, 2011

installation view: Hopkinson Cundy, Auckland

Nicola Farquhar

New Paintings, 2011

installation view: Hopkinson Cundy, Auckland

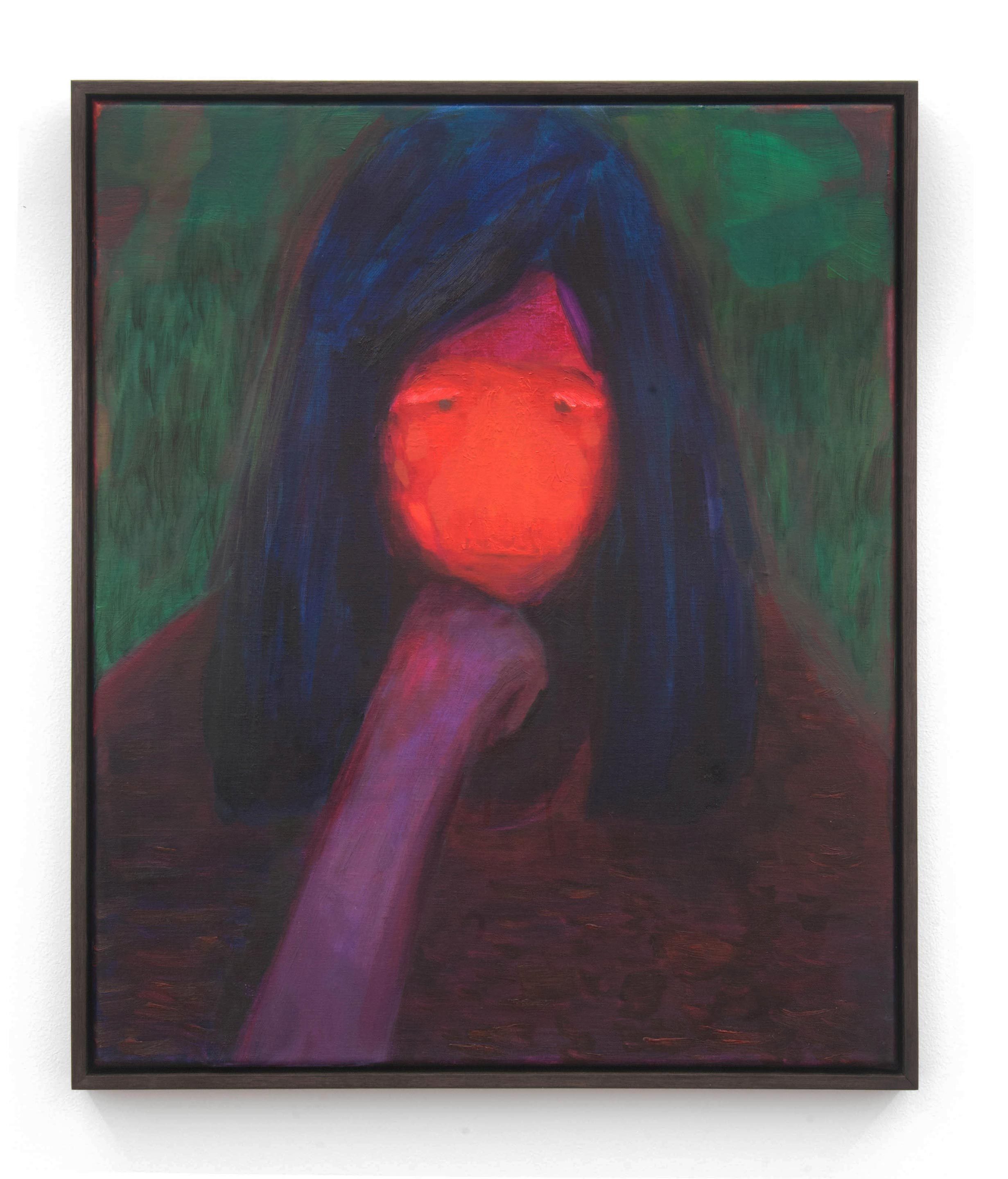

Nicola Farquhar

Shireen, 2011

oil on canvas

600 x 460mm

Nicola Farquhar

Paula, 2011

oil on canvas

400 x 350mm

Nicola Farquhar

New Paintings

06 Oct – 05 Nov 2011

Auckland

Hopkinson Cundy is pleased to present a solo exhibition of new work by Nicola Farquhar.

Continuing her ongoing investigation into the portrait form, each of Farquhar’s paintings feature a female head and shoulders at either frontal or three-quarter view. Farquhar’s portraits are based on memories of girls she knew in her youth, yet the forms are honed intuitively with little in the way of pre-conceived ideas or sketches. For Farquhar painting is a process of building or re-building people; guided by her memory of their physical characteristics, she constructs each figure with layered pieces of colour.

Areas of Farquhar’s surfaces are heavily worked and others are left almost untouched. The faces are typically the most densely layered; some features – cheekbones, foreheads, chins – are buried or smudged away, while others – eyes, noses, teeth – are highlighted to disquieting effect. In this recent series the backgrounds and clothing remember earlier forms of modern art (the flat patterning of Synthetism and strong colours of Fauvism, for example) where the faces seem far more ancient and alien. In her essay that accompanies the exhibition Gwynneth Porter says of Farquhar’s women:

They sit still and look out, not exactly disinterested, but unwanting. Their stillness and relative inaction is of the sort of fairytales where everyone sleeps for a hundred years.

New Paintings is Farquhar’s first solo exhibition since graduating from Elam School of Fine Art’s MFA program in 2009. While studying her work was included in exhibitions such as: It can be said that art is what remains after a course of rejection of ideas, Window, Auckland; and Picnic on a Frozen River, projectspace B431, Auckland.

Things are in pieces

The time of these paintings seems ancient. Like mountains, the figures sit powerfully, their action balanced with very dense, heavy repose. That no one posed for these portraits is clear. The colouration of the beings that registered in the paint might describe some sort of Byzantine aura. Or it might be that of birds that live in places so tropical that everything grows horrifically and smells are fetid. Or the colours of small animals that have discovered poison in order not to be eaten, and indicate their decision’s power with their body surface.

Entitlement is so far gone as a necessity for mountains that it is absent, the transaction obsolete. The colours could also be those of orchids for whom procreation is not a request but a fait accompli, an act of manipulation so smooth that no one is disturbed. Consequences for actions are so predictable that everyone relaxes and can sleep deeply. The acid green is like that of jungle foliage, or of mountain lichens, both of which make worlds for smaller, unspeaking beings that have deep calm and a sense of time that opens, closes, folds, stretches and tears.

These female figures seem radical in that their eyes do not drop and their shoulders do not come up when they are regarded. The eyes of predators and thieves drop instead, their volition and power voided. They sit still and look out, not exactly disinterested, but unwanting. Their stillness and relative inaction is of the sort of fairytales where everyone sleeps for a hundred years. They look like nothing threatens them, and that there is no threat in the world. It might be the same world as ours, or might not be. Revolutions are not possible in the same way they used to be. Today they must be conducted on the levels of time and language.

There might be a pictograph for the way a cat communicates with bubbles or head-sized clouds of non-linear information. In the mountains the air is thinner. If you lay still somewhere by the bush-line and listen you can hear the wind rushing over the peaks and it sounds like running water. Dreams of peaks and of vegetated ponds can draw together as if altitude is irrelevant. Sixteen years can elapse and seem like no time at all. In a Cromagnon system, a cave painting can be made by painters working 5,000 years apart, each adding a horse, a bison, or a bear to the interior body at the correct time.

Rightness here is never fearful or tight-fisted, just involving the gentle application of skill. Colour here can look like light. A copper sulphate blue is a suspension of time and of metal salts and the elemental aspect of pigment in oil. Its transparency sits against something dreadfully solid, but the horror is not frightening, just arresting. Some sort of basic character is visible in these young women, their teeth bared, but with no attack. Kissable. The Mona Lisa was really still too, like a sculpture in her objectness. They all have mouths. It is a different image without mouths. They can’t talk, but can’t breathe either or exhale in that way.

If you broke something up it would be colours.

Something’s reality is these pieces of colour.

Gwynneth Porter