Pequod Fiona Amundsen, Luke Willis Thompson, Peter Robinson

Luke Willis Thompson

Untitled (we people who are darker than blue), 2010

collection of artworks from J Weir Funeral Homes, Ponsonby, deconsecrated edition of c-type prints

ten elements: 450 x 450mm (x2), 470 x 570mm (x2), 735 x 1075mm (x4), 575 x 470mm (x2)

Luke Willis Thompson

Untitled (we people who are darker than blue) (detail), 2010

collection of artworks from J Weir Funeral Homes, Ponsonby, deconsecrated edition of c-type prints

735 x 1075mm

Luke Willis Thompson

Untitled (we people who are darker than blue) (detail), 2010

collection of artworks from J Weir Funeral Homes, Ponsonby, deconsecrated edition of c-type prints

450 x 450mm

Luke Willis Thompson

Untitled (we people who are darker than blue) (detail), 2010

collection of artworks from J Weir Funeral Homes, Ponsonby, deconsecrated edition of c-type prints

575 x 470mm

Installation view

Pequod, 2014

Hopkinson Mossman, Auckland

Installation view

Fiona Amundsen, 2014

Hopkinson Mossman, Auckland

Fiona Amundsen

Pathway Through Shinchi Teien (Sacred Pond Garden), Yasukuni Shrine, Tokyo, 14.01.2014, 7.35 (lying still), 2014

inkjet photograph

845 x 1020mm frame

ed. 5 (+1AP)

Fiona Amundsen

Standing At The Edge Of Shinchi Teien (Sacred Pond Garden), Yasukuni Shrine, Tokyo, 13.01.2014, 7.49 (ghostly), 2014

inkjet photograph

845 x 1020mm frame

ed. 5 (+1AP)

Fiona Amundsen

Looking Towards Reijibo Hoanden (Repository For The Symbolic Registers Of Divinities), Yasukuni Shirne, Tokyo, 13.01.2014, 7.44 (seeing spirits)

inkjet photograph

845 x 1020mm frame

ed. 5 (+1AP)

Installation view

Pequod, 2014

Hopkinson Mossman, Auckland

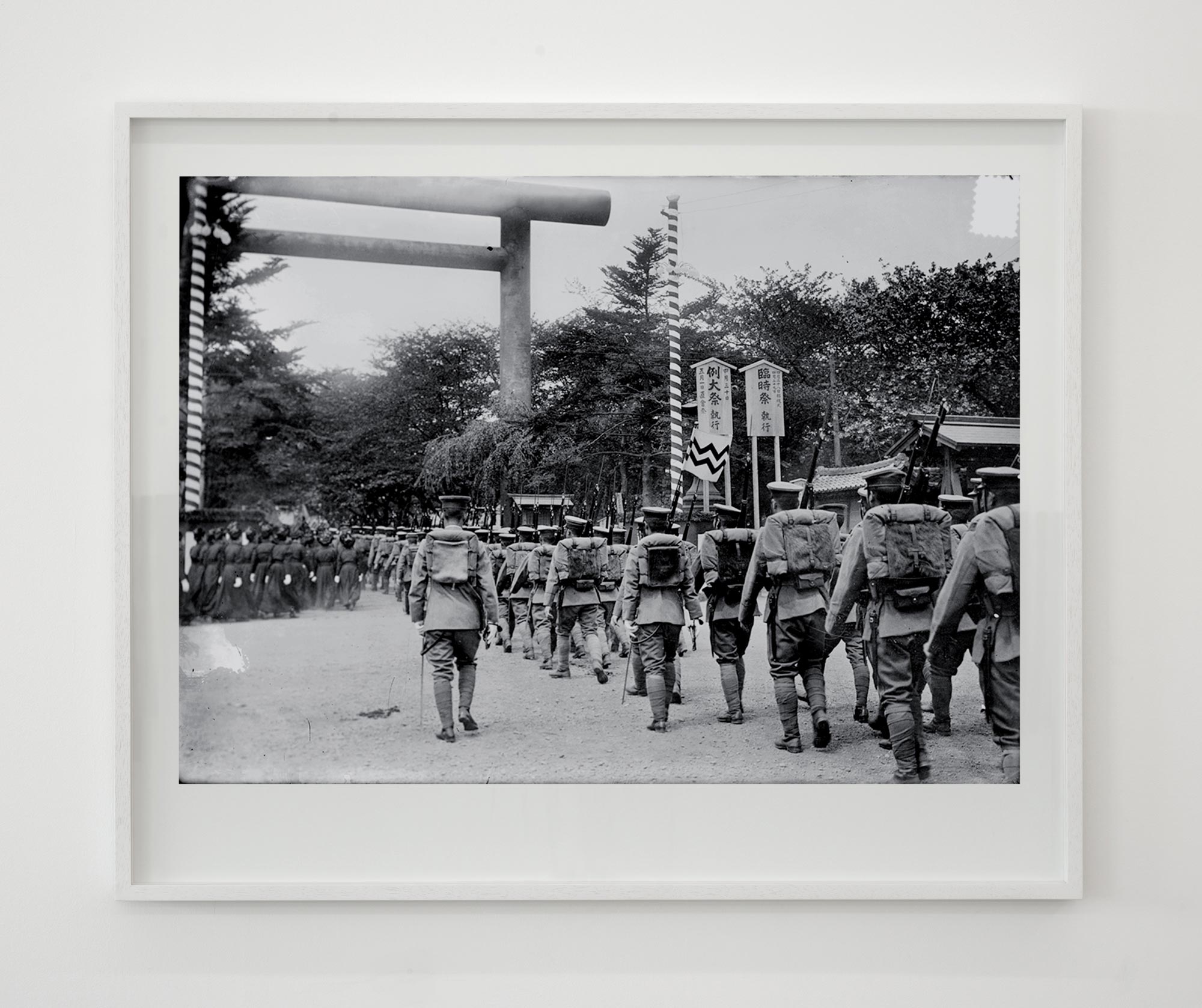

Fiona Amundsen

Soldiers On Their Way to Yasukuni Shrine, Tokyo, 30.11.1941, 9.32 (see the cherry blossom), 2014

inkjet photograph

845 x 1020mm frame

ed. 5 (+1AP)

Installation view

Pequod, 2014

Hopkinson Mossman, Auckland

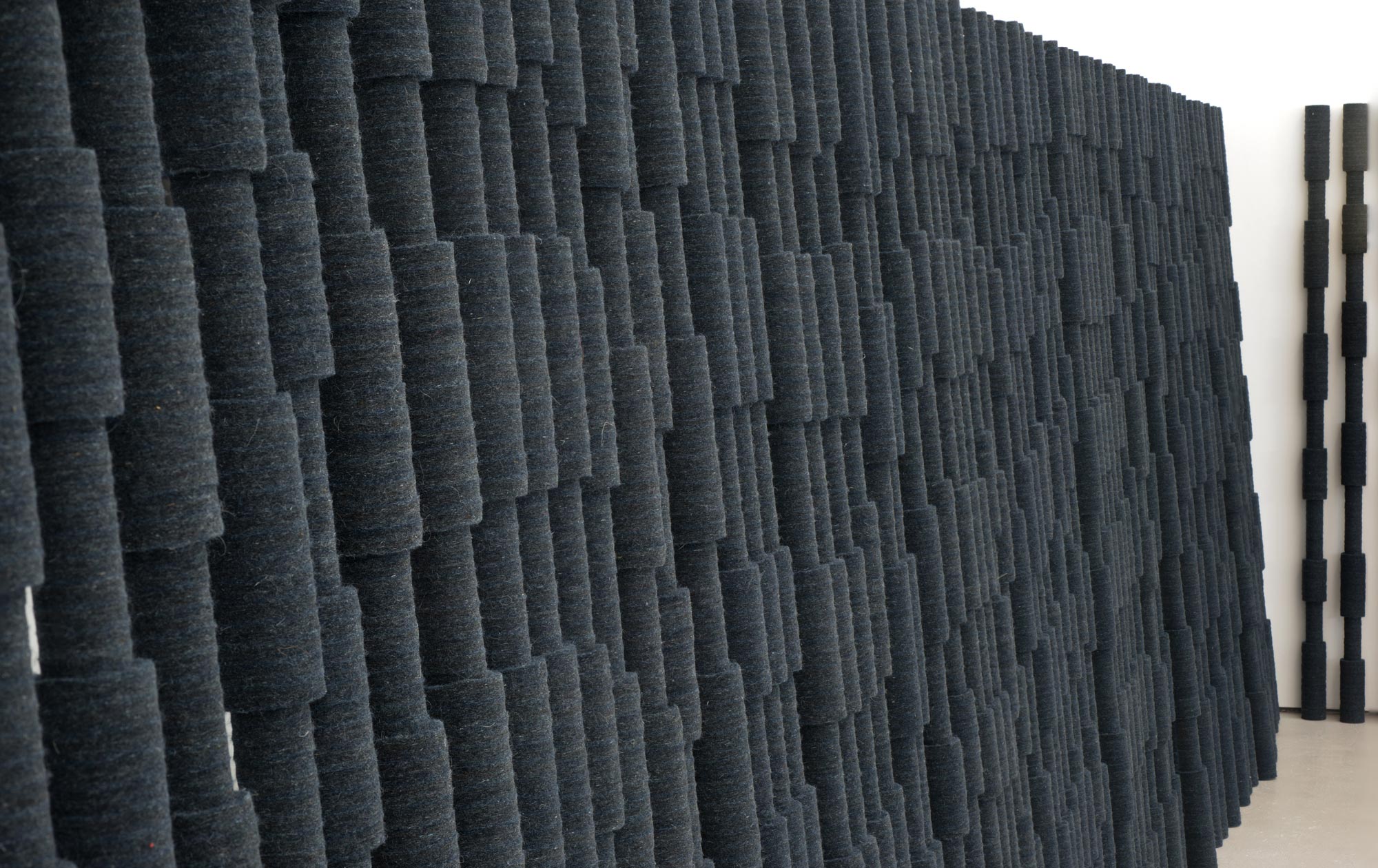

Peter Robinson

Cuts & Junctures, 2013

felt, aluminium

153 elements, either 1270 x 45 x 45mm, 1270 x 90 x 45mm, 1270 x 135 x 45mm, installation dimensions vary (10m span approx)

Peter Robinson

Cuts & Junctures (detail), 2013

felt, aluminium

PEQUOD

Peter Shand

Trauma is by definition overwhelming. It is a totalising experience that bends and reshapes a sense of self to the impact of its effect. Hence people in trauma often act unexpectedly or out of themselves – the passive suddenly roused to action, the strong rendered meek; people in extremis speak of surprise at their actions, whether heroic or cowardly as if our bodies and intentions betray us in moments of extreme provocation.

While it’s not true that the experience of art is the same, there is something akin to the ways in which our experience of art may surprise, undo or reveal to us aspects of who we are that we hadn’t previously appreciated. The involuntary welling of emotion, the feelings of outrage or shock, feelings of worlds compromised or conditions destabilised. It might seem oddly quaint to think we might swoon in the presence of art in the manner of Stendhal but it is foolish, perhaps counter to art’s most significant quality, to refuse this, its capacity for affect.

An interesting tension exists between the seemingly oceanic notion of trauma, grief, emotional upheaval and affect and the precision of much contemporary practice that engages with these most fluid and unruly experiences. Like atolls seeming to rest on the surface of deep emotions, contemporary works of art offer such points of connection without stating what it is they convey. They do not re-present sites, experiences or objects that contain such feelings as much as they reveal artists’ awareness that the capacity to become undone harbours in the artwork.

Affect is dormant or not quite, at least not exactly activated by the sensitive. Rather, it lies in wait, like something present under the surface, beyond the immediately recognisable. Perhaps it is for this reason that it contains its own power, unleashed for us in acts of engagement that are to some extent the result of a simultaneity of distinct experiences housed or held in abeyance in the art object.

And in this it may not figure what type of object or material inhabits this curious, unsettling pool. Objects made by the artist’s hand, fashioned to serve points of connection. Objects recovered by an artist, reconfigured whether to concentrate or obscure past relationships or implications. Objects or sites photographed by the artist, where the touch of the photograph may be in spite of rather than contained within its representational capacity. It is, then, less a question of intention or desire so much as the capacity, unbidden, to take us out of ourselves – to move us.

While these are certainly experiences to be had form the work of Peter Robinson, Luke Willis Thompson and Fiona Amundsen, these diverse practices share a quality of precision. In this I don’t mean an exact or delimiting demarcation of what feelings are channelled or what residual emotion may yet lie within the objects they have wrought. Almost the converse, that in the carefully honed and nuanced works is something akin to a telescoping of a physical engagement that renders more unruly, more provoking, more becoming the undeclared, the not physically captured, the affective aspects of these works.

Which makes for a more complex, more ungraspable, more intense and meaningful connection to the provocations stirred by these works. We are rendered uneasy, compelled to response or “swoon” in part because these artists are less interested in the isolated appreciation or analysis of the art they make but more so in the multiple and unraveling connections and relationships they, their work and we are integrally a part of. In conversation with Mary Zournazi, the French philosopher Michel Serres proposes: “It’s not an ontology we need, but a desmology – in Greek desmos means connection, link … What interests me is not so much the state of things but the relationship between them.”

The empathic conversation suggests this kind of proximity. The inter-relation of artwork, artist, audience (and all our several and complex histories, memories and feelings) is no less intimate, no less a condition by which we are, all of us, changed. Not so much ripples in a pond so much as ripples colliding, eddies and undertows that drag us away and force us back to the surface, gasping.

(November 2014)