Tahi Moore Nonsuch Park

Tahi Moore

Nonsuch Park, 2011

installation view: Hopkinson Cundy, Auckland

Tahi Moore

Nonsuch Park, 2011

installation view: Hopkinson Cundy, Auckland

Tahi Moore

Dancers I & II, 2011

uratrans prints in wood frames, Perspex and neon tube

two elements 450 x 580 x 150mm each

Tahi Moore

Friends II, 2011

wood panels, metal sliding door track, fabric

two elements 600 x 930mm and 700 x 2400mm

Tahi Moore

Friends II (detail), 2011

wood panels, metal sliding door track, fabric

two elements 600 x 930mm and 700 x 2400mm

Tahi Moore

Friends II, 2011

wood panels, metal sliding door track, fabric, two elements

600 x 930mm and 700 x 2400mm

Tahi Moore

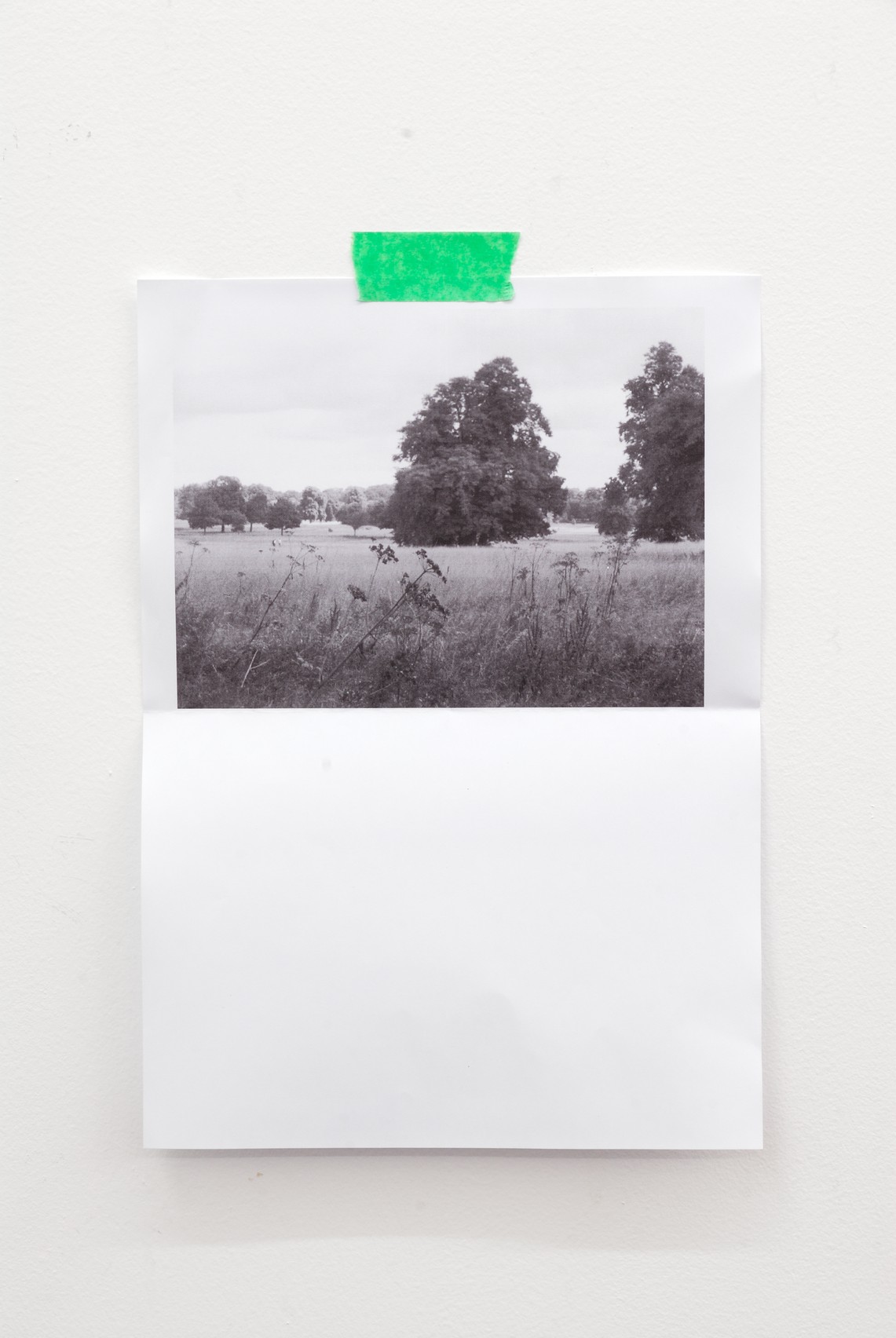

Entrance to Nonsuch Park, 2011

three A4 laser prints with masking tape

290 x 210mm each

Tahi Moore

Nonsuch Park

30 Jun – 30 Jul 2011

Auckland

“I have no idea, following a movie frame of an empty room when Jane Birkin has just left, to images of Birkin bags, to a tattoo on Birkin’s second daughter’s arm of the scrawled word Marlowe, to the murder of Christopher Marlowe by his patron’s servant and the proximity to the Queen at Nonsuch Palace prompting the royal coroner’s investigation, the Star Chamber where Marlowe was questioned, their ruins, Nonsuch is now a field, the Star Chamber is a small wedding reception room in a beach hotel outside of Liverpool, Marlowe and the School of Night, Philip Marlowe finding nothing, Raymond Chandler drinking in the Bristol Hotel, Malone in the Bristol Hotel in Poland, the shift in the pulp novel from the primacy of the denouement to the plot as a background for scenes of the matrix of what you know you want, what you know you don’t want, what you don’t know you don’t want, and what you don’t know you want.”

Hopkinson Cundy is pleased to present a solo exhibition by Tahi Moore opening Wednesday 29 Jun 2011. Nonsuch Park is Moore’s first show at the gallery and will include a new series of video, sculpture and painting.

Tahi Moore graduated with a BFA from Elam School of Fine Art in 2005 and currently lives and works in Auckland. Recent exhibitions include: Caraway Downs, Artspace, Auckland (2011); War against the self, Gambia Castle, Auckland (2010); Vaccum Idle Adjust (with Rob Hood), Enjoy Public Art Gallery, Wellington (2009); and Various Failures, Gambia Castle, Auckland (2008). Recent performances include: Nothing was going on, it was boring anyway, Moment Making, Artspace, Auckland (2007); A movie that isn’t really good, but is o.k. (with Simon Denny), 54321: Artists Projects, Auckland Art Gallery, Auckland (2006); and Mostly Harmless, Govett-Brewster Art Gallery, New Plymouth (2006).

“…unlawful things,

Whose deepness doth entice such forward wits,

To practise more than heavenly power permits.”

Nonsuch Park, in the connection through which Tahi Moore comes to it, is a gap; that is to say, the location of something missing. In the concatenation of things the artist lists in the text accompanying his exhibition invitation, the park follows the Star Chamber. The structure whose design gave its name to that English court of law, once built there, is today long gone. This vacant space could also be considered as an opening, as is proper to a title, a way into understanding the works the artist presents under it.

The proper name almost, but not quite, describes the inconclusiveness that is also and at the same time the momentum of the artist’s work, keeping it unending and free from ends. In researching the site of Christopher Marlowe’s interrogation, he discovers that there, now, there is no such room. Noticing this, both the symbolic approximation and the absence might amplify the visibility of others in these pieces and their derivation: The stretch involved in moving from the word “marlowe” as tattooed on Lou Doillon’s arm to considering the political trouble that surrounded the end of a Renaissance Man’s life, for instance, or between Bret Easton Ellis’s novel Less Than Zero and Hüsker Dü’s track Don’t Want to Know If You Are Lonely playing in a gallery.

On the one hand, such connections should be acknowledged simply as the imaginative leaps traditional to the artist’s work. Species of metaphor, they are the specialized extension of a cognitively fundamental human ability to associate one thing with another, which allows us to make sense of experience through sometimes arbitrary signs. Thus we might see that an artist can find herself in the position of Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus, at the end of accepted fields of knowledge, dabbling beyond them in the darker arts that involve, as Faustus puts it, “Lines, circles, signs, letters and characters”. In his opening soliloquy, Marlowe’s character also refers to the magician who does this as “artisan”, an old word for artist.

The idea that abandoning established reason makes more sense has a significant heritage in modern art. The Comte de Lautréamont’s analogy for the beauty of a boy, being like “la rencontre fortuite sur une table de dissection d’une machine á coudre et d’un parapluie” [the chance meeting on a dissection table of a sewing machine and an umbrella] (Les Chants de Maldoror, 1869), is an infamous example of a far-fetched comparison that the André Breton came to admire as a model for the sort that can revel a deeper truth. In music, aleartoric techniques have been employed as a compositional devices also considered, in a different way, truer to reality, for example.

Moore highlights a possible affinity with Surrealism when he makes it clear that his line of inquiry is to some extent beyond him: “I have no idea….” But there is also a mathematical overtone to the character of the gaps between the images, words and genres he invokes that is distinctly post-conceptual. The way in which the one word “marlowe” refers to various real and imagined people, for example, the associations he makes – following a single textual string to various referents – presents me with Wikipedia, without its distinctive step of “disambiguation”, or Google search results, before I click through to the most promising.

When but via the internet would a society pages photograph featuring jean shorts and tights be brought together with Elizabethan politics? What Nonsuch Park offers me, is neither Moore’s unconscious nor the world unmediated, but their enmeshment, and so my own with, for example, the internet. Google itself tells me that the verb to google entered the dictionary in its contemporary sense as long ago as 2006, but at some point since then, I assume, I have stopped making the self-conscious jokes I once made about my daily recourse to it to find things out. The array of references and the desires that set them adrift in Moore’s art invite me to consider some of the things that are hardest to see about this mundane activity.

It would be too cute to suggest that the constantly developing algorithms that power search engines revive Doctor Faustus’s moral questions about knowledge, and the potential to overreach divinely instituted bounds, and they do not. But the scale of London in the late sixteenth century and the world shrunk by the internet are nonetheless an interesting comparison, not least for the way that scope of disciplines seem blurry in both. I like the story that Philippe Soupault discovered the copy of Les Chants de Maldoror that made it known to his circle, mis-filed, in the mathematics section of a second hand bookshop, a chance meeting of a particular sort in itself. Perhaps, as Moore also writes, “Nonsuch is now a field”.

Jon Bywater, June 2011